Myths and Misconceptions? Get the Facts!

- HEALTHY SCHOOL HOURS MAKE ECONOMIC SENSE.

- GROWING TEEN BRAINS AND BODIES NEED HEALTHY "WAKE-UP" TIMES.

- PREPARING TEENAGERS FOR THE "REAL WORLD" INCLUDES GETTING HEALTHY SLEEP.

- WHEN SCHOOLS START LATER, STUDENT BEDTIMES STAY THE SAME.

- HEALTHY BED TIMES AND OTHER GOOD HABITS ARE IMPORTANT -- BUT SO ARE HEALTHY WAKE TIMES.

- CHILDREN OF ALL AGES, INCLUDING TEENAGERS, NEED SCHOOL HOURS THAT ALLOW FOR HEALTH AND SAFETY.

- WHEN SCHOOLS START AT HEALTHIER HOURS, EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES ADJUST AND THRIVE.

- STUDENTS HAVE AFTER-SCHOOL JOBS NO MATTER WHAT TIME SCHOOL STARTS (OR ENDS).

- WHILE LOCAL SCHOOLS SET INDIVIDUAL HOURS, STATE OR FEDERAL STANDARDS CAN ENSURE THEY WILL BE SAFE AND HEALTHY.

- SCHOOLS BEFORE THE 1970S AND 1980S DID NOT START SO EARLY IN THE MORNING.

- LATER START TIMES ARE NO WORSE FOR WORKING PARENTS THAN CURRENT START TIMES.

- SCHOOL STARTS ARE MORE THAN JUST ABOUT GOOD GRADES

- COMMUNITY LIFE (INCLUDING CHILDCARE) ADJUSTS TO SCHOOL HOURS

- SCHOOL START TIMES ARE A SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSUE

- IS THERE A LIST OF HOW MANY SCHOOL DISTRICTS HAVE CHANGED START TIMES?

HEALTHY SCHOOL HOURS MAKE ECONOMIC SENSE

Every community, large or small, can find many, often hundreds of, ways to run schools at later, healthier hours. Some of these ways may involve re-routing or adding buses, and sometimes this will involve one-time or even recurrent costs. However, every community that has made healthy hours a priority has found a way to change schedules in a cost-efficient way, whether or not new bus costs were involved. Communities that have put student health and well-being first have found a variety of creative solutions, sometimes even saving money in the process. Below are just a few examples:

Other "out-of-box" solutions are out there, including, but not limited to:

The economic benefits to the community at large from running schools at heallthier hours also far outweigh any added transporation costs, even when they do occur. A 2017 report by the RAND Corporation found that moving all middle and high schools to 8:30 a.m. start times or later would bring enormous economic benefits to communities and states--in as little as two years:

Every community, large or small, can find many, often hundreds of, ways to run schools at later, healthier hours. Some of these ways may involve re-routing or adding buses, and sometimes this will involve one-time or even recurrent costs. However, every community that has made healthy hours a priority has found a way to change schedules in a cost-efficient way, whether or not new bus costs were involved. Communities that have put student health and well-being first have found a variety of creative solutions, sometimes even saving money in the process. Below are just a few examples:

Other "out-of-box" solutions are out there, including, but not limited to:

- Santa Rosa County (FL) school district saved millions when it changed to later school start times in 2006. High schools start between 9 and 9:25 a.m. Elementary schools start at 7:30 a.m. This is a very highly ranked Florida public school system with competitive (football district champion!) athletic teams.

- The Wilton (CT) School District maintained its three-tiered bus schedule (which is generally thought to save money), and achieved a more appropriate starting time for teenagers by flipping the upper elementary start, at 8:15 a.m., with the 7:35 a.m middle school/high school start.

- Schools in Moore County, NC created a dual-route bus system in 2009 in which elementary schools and high schools share buses on separate routes. School officials estimate that the changes save about $700,000 a year. The plan shifted high school start times 45 minutes later, with school beginning at 9 am and dismissing at 4 p.m.

- West Des Moines School District in IA found a way to start high schools later by reducing the number of buses needed, saving the district $700,000 annually.

- In the Mahtomedi School District (MN), high schools found a way to start 35 minutes later by shortening passing periods, another no cost solution. An added bonus: no impact on after-school activities, better attendance, and less sleeping in class.

- Jessamine County, KY moved its high school start from 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. without adding bus drivers. Middle schools now start at 8:50 a.m. and elementary schools at 8 a.m.

- Arlington, VA changed high school start times from 7:30 a.m. to 8:19 a.m. without increased expenditure of resources.

- Fairfax County Public Schools in VA have been provided with both low-cost and no-cost options to move their high school start times to 8:00 a.m. or later by an independent consultant. In fall 2014 they chose a plan costing $4.9 million, a cost amounting to about 27 cents per student.

- Every single public school in Ohio that switched to later hours due to sleep research (with the exception of Parma, which did so primarily to save money) did so at no cost, or, in some cases, cost savings.

- Consolidating busing to provide service more efficiently where it is actually being used

- Providing sidewalks, safer paths, and walkways to allow more students the ability to walk or bike to school during daylight hours

- Allowing for online class periods or "virtual learning"

- Providing elective bus service, where riders pay for bus service

- Replacing private bus service with public transportation

The economic benefits to the community at large from running schools at heallthier hours also far outweigh any added transporation costs, even when they do occur. A 2017 report by the RAND Corporation found that moving all middle and high schools to 8:30 a.m. start times or later would bring enormous economic benefits to communities and states--in as little as two years:

- The study suggested that delaying school start times to 8:30 a.m. is a cost-effective, population-level strategy which could have a significant impact on public health and the U.S. economy.

- The study suggested that the benefits of later start times far out-weigh the immediate costs. Even after just two years, the study projects an economic gain of $8.6 billion to the U.S. economy, which would already outweigh the costs per student from delaying school start times to 8:30 a.m.

- After a decade, the study showed that delaying schools start times would contribute $83 billion to the U.S. economy, with this increasing to $140 billion after 15 years. During the 15 year period examined by the study, the average annual gain to the U.S. economy would about $9.3 billion each year.

- Throughout the study's cost-benefit projections, a conservative approach was undertaken which did not include other effects from insufficient sleep, such as higher suicide rates, increased obesity and mental health issues — all of which are difficult to quantify precisely. Therefore, it is likely that the reported economic benefits from delaying school start times could be even higher across many U.S. states.

GROWING TEEN BRAINS AND BODIES NEED HEALTHY "WAKE-UP" TIMES.

Requiring high schools to start after 8:30 or 9:00 a.m. is no more coddling kids than installing car seats or booster seats in automobiles or eliminating indoor smoking in public locations. The latter interventions were originally seen as inappropriate and unnecessary but, with newer research, came to be viewed as mainstream public health measures. There is now ample evidence showing that taking steps to ensure safe, health school hours is no different.

Children might be said to be "coddled" when a parent or caregiver gives them something they don't really need merely to pacify them. Ensuring conditions that allow enough sleep is hardly in this category. Sleep is just as necessary as nutrition and exercise. And early school hours make adequate sleep impossible for many if not most adolescent students. One has to ask why it seems acceptable, even praiseworthy, to ensure that children have physical activity and enough to eat, but somehow indulgent to ensure that they have enough sleep.

Requiring high schools to start after 8:30 or 9:00 a.m. is no more coddling kids than installing car seats or booster seats in automobiles or eliminating indoor smoking in public locations. The latter interventions were originally seen as inappropriate and unnecessary but, with newer research, came to be viewed as mainstream public health measures. There is now ample evidence showing that taking steps to ensure safe, health school hours is no different.

Children might be said to be "coddled" when a parent or caregiver gives them something they don't really need merely to pacify them. Ensuring conditions that allow enough sleep is hardly in this category. Sleep is just as necessary as nutrition and exercise. And early school hours make adequate sleep impossible for many if not most adolescent students. One has to ask why it seems acceptable, even praiseworthy, to ensure that children have physical activity and enough to eat, but somehow indulgent to ensure that they have enough sleep.

PREPARING TEENAGERS FOR THE "REAL WORLD" INCLUDES GETTING HEALTHY SLEEP.

Although many people seem to think otherwise, teenagers are still children - and growing ones at that. They are not adults, and their growing brains and bodies need on average 8.5 - 9.25 hours of sleep per night. Many teens simply cannot fall asleep before 11 p.m., due to shifted circadian rhythms (body clocks). Yes, poor planning, electronic and other distractions, and poor parenting can certainly contribute to the problem, but the fact that these circadian rhythm shifts appear in adolescent mammals as well as adolescent humans suggests that there's more to the story here than irresponsibility.

This is not a matter of will. It's a matter of biology. Allowing teenagers to drive while sleep deprived to teach them responsibility is comparable to giving a drunk driver keys to his car and expecting him to be responsible about it. And just because something must be done at a later point in life does not make it appropriate earlier in life. Asking teenagers to deprive themselves of sleep to "prepare" for the real world is like asking toddlers to skip their naps to prepare for fifth grade.

Secondary school also have some very significant differences with both college, military service, or employment. Very few colleges start classes before 8 a.m., and most colleges give students the option of choosing classes that start later in the day. Very few jobs run from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m. either, nor do they involve doing calculus at 7 a.m. or going home with hours or homework every night. Furthermore, most people have some degree of choice in the hours they keep as adults. Middle and high school students are required by law to keep to schedules set by their school systems unless they have the means to home school or attend a private school.

The "real world" is a diverse place, with hours and schedules differing varying greatly from person to person, job to job, lifestyle to lifestyle. None of these "real worlds" is exactly like that of the world of a high school student, nor is it necessary to wake up extremely early throughout middle and high school just because you might have to, or choose to, wake up early years later. You don't have to train for sleep deprivation. For a humorous take on what it REALLY takes to "prepare" students for the "real world," check out this commentary (warning: adult language):

The Real World - Swankington.

Although many people seem to think otherwise, teenagers are still children - and growing ones at that. They are not adults, and their growing brains and bodies need on average 8.5 - 9.25 hours of sleep per night. Many teens simply cannot fall asleep before 11 p.m., due to shifted circadian rhythms (body clocks). Yes, poor planning, electronic and other distractions, and poor parenting can certainly contribute to the problem, but the fact that these circadian rhythm shifts appear in adolescent mammals as well as adolescent humans suggests that there's more to the story here than irresponsibility.

This is not a matter of will. It's a matter of biology. Allowing teenagers to drive while sleep deprived to teach them responsibility is comparable to giving a drunk driver keys to his car and expecting him to be responsible about it. And just because something must be done at a later point in life does not make it appropriate earlier in life. Asking teenagers to deprive themselves of sleep to "prepare" for the real world is like asking toddlers to skip their naps to prepare for fifth grade.

Secondary school also have some very significant differences with both college, military service, or employment. Very few colleges start classes before 8 a.m., and most colleges give students the option of choosing classes that start later in the day. Very few jobs run from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m. either, nor do they involve doing calculus at 7 a.m. or going home with hours or homework every night. Furthermore, most people have some degree of choice in the hours they keep as adults. Middle and high school students are required by law to keep to schedules set by their school systems unless they have the means to home school or attend a private school.

The "real world" is a diverse place, with hours and schedules differing varying greatly from person to person, job to job, lifestyle to lifestyle. None of these "real worlds" is exactly like that of the world of a high school student, nor is it necessary to wake up extremely early throughout middle and high school just because you might have to, or choose to, wake up early years later. You don't have to train for sleep deprivation. For a humorous take on what it REALLY takes to "prepare" students for the "real world," check out this commentary (warning: adult language):

The Real World - Swankington.

WHEN SCHOOLS START LATER, STUDENT BEDTIMES STAY THE SAME.

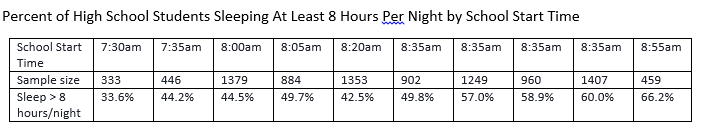

When schools start classes later, more students get more sleep. And contrary to expectation, bedtimes usually stay the same. A little extra time in the morning makes all the difference. The landmark school start time study by Kyla Wahlstrom at the University of Minnesota showed that moving the opening time from 7:15 to 8:40 a.m. resulted in teens getting a full hour of sleep more than students at high schools with earlier start times, with virtually no change in their bedtimes. Several subsequent studies have found the same thing: when schools move to later morning starts, students consistently got more sleep per school night because they went to bed at or near the same time each night and were able to rise later in the morning. And recent data from over 62,000 teenagers around the USA reported in Scientific American confirm that teenagers whose schools start later in the more get more sleep. A 2018 study of Seattle teenagers whose schools moved from 7:50 to *:45 a.m. found the same thing. Full citations and a discussion of this topic are available here. Of course, a later start time is no guarantee that students will get more sleep. Students still need to follow healthy sleep practices, including choosing a reasonable bedtime, and evidence is accumulating that schools that change their start times in conjunction with a sleep education program are more likely to have better outcomes. However, it's important to remember that under current conditions, most students cannot get enough sleep no matter what their sleep habits might be. While changing start times is no guarantee that most students will get enough sleep, not changing them is a guarantee that most of them will not.

When schools start classes later, more students get more sleep. And contrary to expectation, bedtimes usually stay the same. A little extra time in the morning makes all the difference. The landmark school start time study by Kyla Wahlstrom at the University of Minnesota showed that moving the opening time from 7:15 to 8:40 a.m. resulted in teens getting a full hour of sleep more than students at high schools with earlier start times, with virtually no change in their bedtimes. Several subsequent studies have found the same thing: when schools move to later morning starts, students consistently got more sleep per school night because they went to bed at or near the same time each night and were able to rise later in the morning. And recent data from over 62,000 teenagers around the USA reported in Scientific American confirm that teenagers whose schools start later in the more get more sleep. A 2018 study of Seattle teenagers whose schools moved from 7:50 to *:45 a.m. found the same thing. Full citations and a discussion of this topic are available here. Of course, a later start time is no guarantee that students will get more sleep. Students still need to follow healthy sleep practices, including choosing a reasonable bedtime, and evidence is accumulating that schools that change their start times in conjunction with a sleep education program are more likely to have better outcomes. However, it's important to remember that under current conditions, most students cannot get enough sleep no matter what their sleep habits might be. While changing start times is no guarantee that most students will get enough sleep, not changing them is a guarantee that most of them will not.

HEALTHY BED TIMES AND OTHER GOOD HABITS ARE IMPORTANT -- BUT SO ARE HEALTHY WAKE TIMES.

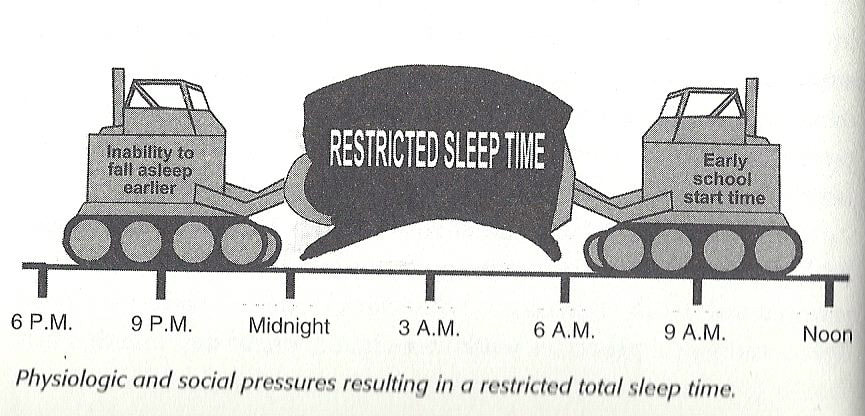

There's no question that student sleep can improve by reducing exposure to distractions, such as TV, cell phones, and computers and following other basic tenets of healthy "sleep hygiene." However, sleep research shows that even teens with impeccable "sleep hygiene" cannot possibly get enough sleep if they need to get up in time to make 7 a.m. school bells or even earlier buses. This is because most simply cannot fall asleep before about until 11 p.m., the time when most teenagers and young adult start producing enough melatonin, the hormone believed to help regulate sleep.

Teenagers require on average 8.5 – 9.25 hours of sleep per night, which is more than most adults require. For a teenager to get enough sleep for a 7:00 a.m. school start or a 5:30 am wake up call, she would have to be in bed and fast asleep by 8:30 p.m. Homework, extracurriculars, and electronics aside, this bedtime is counter to the natural, biological makeup of most high school students. Because of the shifted times in which adolescent brains produce melatonin, even the best laid plans often result in the teenager staring at the ceiling until well after 11 p.m.

The graphic below describes the way early school starts are, by design, creating a nation of sleep deprived teens.

There's no question that student sleep can improve by reducing exposure to distractions, such as TV, cell phones, and computers and following other basic tenets of healthy "sleep hygiene." However, sleep research shows that even teens with impeccable "sleep hygiene" cannot possibly get enough sleep if they need to get up in time to make 7 a.m. school bells or even earlier buses. This is because most simply cannot fall asleep before about until 11 p.m., the time when most teenagers and young adult start producing enough melatonin, the hormone believed to help regulate sleep.

Teenagers require on average 8.5 – 9.25 hours of sleep per night, which is more than most adults require. For a teenager to get enough sleep for a 7:00 a.m. school start or a 5:30 am wake up call, she would have to be in bed and fast asleep by 8:30 p.m. Homework, extracurriculars, and electronics aside, this bedtime is counter to the natural, biological makeup of most high school students. Because of the shifted times in which adolescent brains produce melatonin, even the best laid plans often result in the teenager staring at the ceiling until well after 11 p.m.

The graphic below describes the way early school starts are, by design, creating a nation of sleep deprived teens.

CHILDREN OF ALL AGES, INCLUDING TEENAGERS, NEED SCHOOL HOURS THAT ALLOW FOR HEALTH AND SAFETY.

Many school systems currently start high schools first and then recirculate buses two or three times to ferry middle and elementary school students to school later in the morning - an efficient and cost-saving approach. It is often suggested that high school and elementary schools hours be flipped so that high schools can start later at no additional cost. Such proposals usually meet with huge public outcry about the dangers of having first graders standing outside waiting for buses at 6 a.m.

What is overlooked in this outcry is that it is also unsafe to have 15-year-old girls standing on dark corners alone at 6 a.m. or to send new, sleep-deprived teen drivers out onto the roads at that time. A 2011 study, for example, found that the weekday crash rate among high schoolers in Virginia Beach, where classes began at 7:20-7:25 a.m. was significantly higher than in adjacent Chesapeake, VA, where classes started at 8:40-8:45. Another study in Fayette County, KY linked a move to a later high school start time to a drop in the rate of teen car crashes.

It’s not safe for any child, even a high school student, to walk to school or wait for buses in the dark. Age does nothing to make pedestrians more visible to drivers. Transportation departments should work to arrange bus runs and school opening times to keep ALL students safe, not just the youngest ones. The following stories point to tragedies that could have been averted with a later school start time. The cost of continuing to ignore the safety risks with early school start times is a high price to pay. Below is just a sampling of safety incidents:

In Cary, NC, a 12-year old boy was struck prior to 7:00a.m. at his bus stop. A 13-year old girl in Fall River, MA was struck near her bus stop at 6:23a.m. More recently, a 9 year old girl was struck and killed in Westwood, OH in the early morning darkness while waiting for her bus.

Additionally, the early morning hours pose other risks to children. In Fairfax, VA, a 15 year old girl was sexually assaulted while waiting at her school bus stop at 6:20a.m.

In October 2012, a 16-year old student was killed when attempting to walk in pre-dawn, overcast conditions to her high school in Germantown, MD.

In December 2012, a student attempting to get to school in Laurel, MD during predawn hours was killed. This marks the third student pedestrian fatality at Fort Meade High School in Anne Arundel County, MD. in the school year.

In March 2013, a student was struck and injured by a vehicle while walking to school in the early morning in Watkins Mill, MD. A 55-year old man was killed in Gaithersburg, MD by a school bus traveling on a busy intersection at 6:30am only a week later.

In April 2013, a Houston, TX area student was struck and killed on his way to school on a dark morning.

A Florida student was struck and killed in August 2013 as he made his way to school at 6:20am.

A Charlotte, NC student was struck by a vehicle in September 2013 while waiting for his school bus at 6:15am. While that student only sustained minor injuries, another high school student was killed while traveling during pre-dawn hours in West Rowan County, North Carolina in October 2013.

In October 2018, four students waiting for a bus at 7:00a.m. in Aspen Hill, MD were struck by a car, with one student having life-threatening injuries.

Ensuring the safety of our children and others by eliminating early, darkened, unsafe bus stops and walking routes must become more of a priority than the expense of bus runs.

Many school systems currently start high schools first and then recirculate buses two or three times to ferry middle and elementary school students to school later in the morning - an efficient and cost-saving approach. It is often suggested that high school and elementary schools hours be flipped so that high schools can start later at no additional cost. Such proposals usually meet with huge public outcry about the dangers of having first graders standing outside waiting for buses at 6 a.m.

What is overlooked in this outcry is that it is also unsafe to have 15-year-old girls standing on dark corners alone at 6 a.m. or to send new, sleep-deprived teen drivers out onto the roads at that time. A 2011 study, for example, found that the weekday crash rate among high schoolers in Virginia Beach, where classes began at 7:20-7:25 a.m. was significantly higher than in adjacent Chesapeake, VA, where classes started at 8:40-8:45. Another study in Fayette County, KY linked a move to a later high school start time to a drop in the rate of teen car crashes.

It’s not safe for any child, even a high school student, to walk to school or wait for buses in the dark. Age does nothing to make pedestrians more visible to drivers. Transportation departments should work to arrange bus runs and school opening times to keep ALL students safe, not just the youngest ones. The following stories point to tragedies that could have been averted with a later school start time. The cost of continuing to ignore the safety risks with early school start times is a high price to pay. Below is just a sampling of safety incidents:

In Cary, NC, a 12-year old boy was struck prior to 7:00a.m. at his bus stop. A 13-year old girl in Fall River, MA was struck near her bus stop at 6:23a.m. More recently, a 9 year old girl was struck and killed in Westwood, OH in the early morning darkness while waiting for her bus.

Additionally, the early morning hours pose other risks to children. In Fairfax, VA, a 15 year old girl was sexually assaulted while waiting at her school bus stop at 6:20a.m.

In October 2012, a 16-year old student was killed when attempting to walk in pre-dawn, overcast conditions to her high school in Germantown, MD.

In December 2012, a student attempting to get to school in Laurel, MD during predawn hours was killed. This marks the third student pedestrian fatality at Fort Meade High School in Anne Arundel County, MD. in the school year.

In March 2013, a student was struck and injured by a vehicle while walking to school in the early morning in Watkins Mill, MD. A 55-year old man was killed in Gaithersburg, MD by a school bus traveling on a busy intersection at 6:30am only a week later.

In April 2013, a Houston, TX area student was struck and killed on his way to school on a dark morning.

A Florida student was struck and killed in August 2013 as he made his way to school at 6:20am.

A Charlotte, NC student was struck by a vehicle in September 2013 while waiting for his school bus at 6:15am. While that student only sustained minor injuries, another high school student was killed while traveling during pre-dawn hours in West Rowan County, North Carolina in October 2013.

In October 2018, four students waiting for a bus at 7:00a.m. in Aspen Hill, MD were struck by a car, with one student having life-threatening injuries.

Ensuring the safety of our children and others by eliminating early, darkened, unsafe bus stops and walking routes must become more of a priority than the expense of bus runs.

WHEN SCHOOLS START AT HEALTHIER HOURS, EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES ADJUST AND THRIVE.

Schools start and end at very different times all over the country (and the world). Whether they dismiss at 1:40 p.m. or 3:30 p.m., schools manage to support athletics and other extracurricular activities. When communities change their school hours, the whole community adjusts accordingly. This is precisely what happened when many schools moved start times earlier in the 1980’s. Just because something is done a certain way now doesn’t mean it’s the only, or the best, way to do things.

The evidence bears this out: starting school after 8:30 a.m. does not harm, and may even help, extracurricular performance. Here are just a few examples from the world of sports:

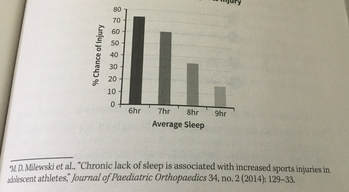

None of this even considers the potential benefits to athletes (or anyone!) of getting enough sleep. A Stanford University study, released in March 2011 found that athletes who sleep more perform better, and a 2014 study published in the Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics showed that young competitive athletes who slept eight or more hours each night were 68 percent less likely to be injured than athletes who regularly slept less. That is part of the reason why coaches from schools that have moved the school day later have surprisingly positive things to say about the change.

Sleep Loss and Athletic Injuries in Adolescents

Schools start and end at very different times all over the country (and the world). Whether they dismiss at 1:40 p.m. or 3:30 p.m., schools manage to support athletics and other extracurricular activities. When communities change their school hours, the whole community adjusts accordingly. This is precisely what happened when many schools moved start times earlier in the 1980’s. Just because something is done a certain way now doesn’t mean it’s the only, or the best, way to do things.

The evidence bears this out: starting school after 8:30 a.m. does not harm, and may even help, extracurricular performance. Here are just a few examples from the world of sports:

- After Wilton, CT pushed their school start time later, the school won several state championships.

- Loudon County, VA has a top ranked football and girls soccer program with athletes earning athletic scholarships. The starting bell at Loudoun high schools is 9:00 a.m.

- The high school start times for members of the Parade's All-America Football Team shows that athletic excellence is possible regardless of school start time. Twenty of the star athletes go to schools that start at 8:00 a.m. or later. 13 start earlier than 8:00 a.m. The remaining 13 athletes did not have start times available.

None of this even considers the potential benefits to athletes (or anyone!) of getting enough sleep. A Stanford University study, released in March 2011 found that athletes who sleep more perform better, and a 2014 study published in the Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics showed that young competitive athletes who slept eight or more hours each night were 68 percent less likely to be injured than athletes who regularly slept less. That is part of the reason why coaches from schools that have moved the school day later have surprisingly positive things to say about the change.

Sleep Loss and Athletic Injuries in Adolescents

STUDENTS HAVE AFTER-SCHOOL JOBS NO MATTER WHAT TIME SCHOOL STARTS (OR ENDS).

Schools start and end at many different times around the USA, and around the world, and communities adapt to these hours - not vice versa. Even if starting the day later means dismissing students at 3 or 3:30 or even 4 p.m., there is still plenty of time for after-school employment. Very few teenagers start jobs before these hours as it is; most work in the late afternoons, early evenings, and on weekends, whether school dismisses at 1:45 p.m. or 4:30 p.m. Even those few employers who took advantage of 2 p.m. dismissals may have to shift work hours slightly, but they do this by necessity if they want to keep their labor force.

The fact that teenagers in communities that already start and end the school day on the later side still have after-school jobs prove that this objection is only a problem if the change is made too quickly, without giving the employers time to adjust. A study conducted by the Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement at the University of Minnesota, moreover, confirmed this, citing local employers who said that that later school hours did not affect their businesses or the amount of hours that students were available for work.

Students who are compelled to work long hours to help support their families are also particularly hurt when school starts too early in the morning. It is not unusual for these students to have to work until 10 or 11 p.m., which makes it very hard for them to wake at 5 or 6 in the morning for school. The result for many of these teenagers is that they not only end up being chronically sleep deprived but also are much more likely to be tardy or truant than their classmates, and many may even find it hard to stay in school. In fact, some studies have shown that students who work many hours per week sleep significantly less than their classmates. At a very diverse high-needs school in Northern Virginia, for example, students working 20 or more hours per week averaged 37 minutes less sleep per school night than non-working students.

Of course when families genuinely depends on a students working long hours, school systems can also use waivers to accommodate their needs without subjecting the entire student body to unsafe, unhealthy, and counterproductive hours.

Schools start and end at many different times around the USA, and around the world, and communities adapt to these hours - not vice versa. Even if starting the day later means dismissing students at 3 or 3:30 or even 4 p.m., there is still plenty of time for after-school employment. Very few teenagers start jobs before these hours as it is; most work in the late afternoons, early evenings, and on weekends, whether school dismisses at 1:45 p.m. or 4:30 p.m. Even those few employers who took advantage of 2 p.m. dismissals may have to shift work hours slightly, but they do this by necessity if they want to keep their labor force.

The fact that teenagers in communities that already start and end the school day on the later side still have after-school jobs prove that this objection is only a problem if the change is made too quickly, without giving the employers time to adjust. A study conducted by the Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement at the University of Minnesota, moreover, confirmed this, citing local employers who said that that later school hours did not affect their businesses or the amount of hours that students were available for work.

Students who are compelled to work long hours to help support their families are also particularly hurt when school starts too early in the morning. It is not unusual for these students to have to work until 10 or 11 p.m., which makes it very hard for them to wake at 5 or 6 in the morning for school. The result for many of these teenagers is that they not only end up being chronically sleep deprived but also are much more likely to be tardy or truant than their classmates, and many may even find it hard to stay in school. In fact, some studies have shown that students who work many hours per week sleep significantly less than their classmates. At a very diverse high-needs school in Northern Virginia, for example, students working 20 or more hours per week averaged 37 minutes less sleep per school night than non-working students.

Of course when families genuinely depends on a students working long hours, school systems can also use waivers to accommodate their needs without subjecting the entire student body to unsafe, unhealthy, and counterproductive hours.

WHILE LOCAL SCHOOLS SET INDIVIDUAL HOURS, STATE OR FEDERAL STANDARDS CAN ENSURE THEY WILL BE SAFE AND HEALTHY.

Many aspects of school policy are regulated by state and federal government, particularly when local school systems cannot or will not set policies to protect basic rights, including rights to health, safety, and education. This has been proven to be the case with respect to the issue of school start times since the 1990's.

Specific school hours must be set locally to reflect specific demographics, topography, values, and budgets. However, establishing a barebones minimum before which schools should not begin mandated instruction is as fundamental as requiring schools to turn on the heat when the temperature falls below a certain level. The idea of setting a minimum standard is simply to provide a boundary to protect children from being forced to adhere to school starts that negatively impact their health and safety. Whether this minimum is set through law, regulation, or guideline, and whether, ultimately, it is set at a federal, state, or even local level, it needs to be established to protect children.

Starting school at later, safe, healthy hours is universally beneficial to all children. This is along the same vein as Child Labor Laws and Child Car Seat Restraint Laws.

The United States has a long history of recognizing the protection of health and safety as a core function of government, and over the years many measures to protect individuals from harm originally thought of as overly intrusive or misguided are now accepted as essential. Many federal mandates have been enacted to ensure minimum levels of health and safety for all children. A few examples are:

The number of state laws to protect child health and safety is even greater, including laws to reduce sodium in food, protect against sports-related traumatic brain injuries, and prevent drunk driving. Nor does setting guidelines for the timing of classes override "local control" of schools. Indeed, states already regulate the number of days per year students must attend school, how many hours a day they must be in class, and even start and finish dates for the school year.

Because many local school districts have competing interests, such as cutting costs, politics and logistics, they have not always put the safety and welfare of children as the utmost priority. This is why a federal mandate or related regulation is a sensible and well-precedented way to preserve the health, safety, and well-being of all children.

Many aspects of school policy are regulated by state and federal government, particularly when local school systems cannot or will not set policies to protect basic rights, including rights to health, safety, and education. This has been proven to be the case with respect to the issue of school start times since the 1990's.

Specific school hours must be set locally to reflect specific demographics, topography, values, and budgets. However, establishing a barebones minimum before which schools should not begin mandated instruction is as fundamental as requiring schools to turn on the heat when the temperature falls below a certain level. The idea of setting a minimum standard is simply to provide a boundary to protect children from being forced to adhere to school starts that negatively impact their health and safety. Whether this minimum is set through law, regulation, or guideline, and whether, ultimately, it is set at a federal, state, or even local level, it needs to be established to protect children.

Starting school at later, safe, healthy hours is universally beneficial to all children. This is along the same vein as Child Labor Laws and Child Car Seat Restraint Laws.

The United States has a long history of recognizing the protection of health and safety as a core function of government, and over the years many measures to protect individuals from harm originally thought of as overly intrusive or misguided are now accepted as essential. Many federal mandates have been enacted to ensure minimum levels of health and safety for all children. A few examples are:

- Federal nutrition standards for school meals

- Federally mandated school wellness policies

- Federal gun free schools / zero tolerance

- Federally approved child-safety seats

- The Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988

The number of state laws to protect child health and safety is even greater, including laws to reduce sodium in food, protect against sports-related traumatic brain injuries, and prevent drunk driving. Nor does setting guidelines for the timing of classes override "local control" of schools. Indeed, states already regulate the number of days per year students must attend school, how many hours a day they must be in class, and even start and finish dates for the school year.

Because many local school districts have competing interests, such as cutting costs, politics and logistics, they have not always put the safety and welfare of children as the utmost priority. This is why a federal mandate or related regulation is a sensible and well-precedented way to preserve the health, safety, and well-being of all children.

SCHOOLS BEFORE THE 1970S AND 1980S DID NOT START SO EARLY IN THE MORNING.

There is a prevailing notion that children should be able to wake and start school earlier because farmers woke early, because children of yesteryear walked long distances to school, and because generations before experienced extreme hardships and survived.

In the case of farmers, while they were up at dawn to perform work, they also had long periods of rest during the day and during the winter season when the ground rested. Additionally, farmers did not have the requirements of homework, sports, and extra-curricular activities in addition to a minimum required number of hours of instructional time that today's children are expected to have in order to gain college admission and compete for gainful employment.

According to the National Research Center for Women and Families, (NRC), most schools in the 1950's and 1960's started between 8:30-9:00 a.m. The extremely early starts to the 7:00 hour were the direct result of staggering start times of high schools, middle schools, and elementary schools in order to utilize fewer buses and drivers. Expecting children to adapt to the demands of rising earlier because that is what was always done is equivalent to expecting children to drink adulterated milk or ride bikes without helmets because that's what children did in the past.

Another fallacy is that conditions today are precisely like those of the past. Yes, many children today still walk to school, but walking today is often in the dark and involves wrestling with high traffic conditions and higher local speed limits that didn't exist in the 1960's and before.

Finally, the "good enough for us" mentality flies in the face of every parent's dream to give his or her children a better future. Farmers worked the soil and many parents sacrificed so their children could have a chance to go to college and have a better future. Most parents do not want their children to just survive. They work hard and raise their children so that their children can thrive. While there are differences of opinion on how parents achieve this, the research is clear: "early school schedules can undermine teenagers’ ability to learn, to drive safely, and to get along with others. They can even increase the likelihood of smoking, drug abuse, and teen pregnancy." (NRC) Remember: just because we can do something, doesn't mean we should.

The facts are clear: We DIDN'T do this (go to school so early), and we are not "just fine."

There is a prevailing notion that children should be able to wake and start school earlier because farmers woke early, because children of yesteryear walked long distances to school, and because generations before experienced extreme hardships and survived.

In the case of farmers, while they were up at dawn to perform work, they also had long periods of rest during the day and during the winter season when the ground rested. Additionally, farmers did not have the requirements of homework, sports, and extra-curricular activities in addition to a minimum required number of hours of instructional time that today's children are expected to have in order to gain college admission and compete for gainful employment.

According to the National Research Center for Women and Families, (NRC), most schools in the 1950's and 1960's started between 8:30-9:00 a.m. The extremely early starts to the 7:00 hour were the direct result of staggering start times of high schools, middle schools, and elementary schools in order to utilize fewer buses and drivers. Expecting children to adapt to the demands of rising earlier because that is what was always done is equivalent to expecting children to drink adulterated milk or ride bikes without helmets because that's what children did in the past.

Another fallacy is that conditions today are precisely like those of the past. Yes, many children today still walk to school, but walking today is often in the dark and involves wrestling with high traffic conditions and higher local speed limits that didn't exist in the 1960's and before.

Finally, the "good enough for us" mentality flies in the face of every parent's dream to give his or her children a better future. Farmers worked the soil and many parents sacrificed so their children could have a chance to go to college and have a better future. Most parents do not want their children to just survive. They work hard and raise their children so that their children can thrive. While there are differences of opinion on how parents achieve this, the research is clear: "early school schedules can undermine teenagers’ ability to learn, to drive safely, and to get along with others. They can even increase the likelihood of smoking, drug abuse, and teen pregnancy." (NRC) Remember: just because we can do something, doesn't mean we should.

The facts are clear: We DIDN'T do this (go to school so early), and we are not "just fine."

LATER START TIMES ARE NO WORSE FOR WORKING PARENTS THAN CURRENT START TIMES.

For every family concerned that a later start time will hurt their job is one who is hurt right now by the early start times.

Until school and work schedules are perfectly aligned, some families are going to find those schedules problematic. Usually there are solutions to these problems, whether it is private childcare, before and afterschool care, or flexible work hours. The growing acceptability of working at home, chosen by many parents with the option to do so, is also giving many families more flexibility (according to the Pew Research Center, 35% of all workers offered the choice to work remotely full-time did so after the COVID-19 pandemic vs. only 7% pre-pandemic). Regardless, moving a middle or high school time to 8 a.m. or later is not the cause of problems balancing work and school, and, in fact, resolves as many problems as it may seem to cause.

In addition, it’s important to remember that we’re generally talking about starting middle and high schools later. The children concerned are 12 -18 years old, and usually do not need the same kind of parental supervision to get to school that younger children need. The fact that parents concerned about lack of supervision defend 7 a.m. start times, which go hand-in-hand with 2 p.m. dismissal times, or that they defend 7 a.m. start times for teenagers but accept 9:15 a.m. start times for first graders, suggests that the real concern isn’t childcare or work.

Even concerns about driving to work in rush hour are based on entirely unfounded speculation, not only because different families have different hours but because traffic patterns themselves are impacted not just by school hours but by complex adjustments communities make to them. In many communities it is the school buses themselves - and people driving their kids to school, in part to overcome early hours – that create the bulk of the traffic. If school hours shift, so will traffic patterns, so it's hard to say in advance just how any specific school start time relates to "rush hour." Predictions are especially challenging given that in many communities ridership on school buses is low for high schoolers who choose to drive themselves or their friends to avoid the early hours. It's entirely possible that when school hours are later, bus ridership wil increase, relieving a great deal of traffic. This is speculation, but so are fears about gridlock if schools change hours in any way.

For every family concerned that a later start time will hurt their job is one who is hurt right now by the early start times.

- Consider the high school teacher who needs to be at work by 6:30 a.m. but whose elementary school-aged kids don’t start school until 9 or 9:30.

- Consider all the children who come home in the early afternoon to empty houses because parents aren’t back from work until 5:30 or 6 p.m.

- Consider the parents who can’t work at all because of the limited window of time between getting the youngest child to class and the oldest child home. A teen going to school from 7 a.m.-2 p.m., a middle schooler from 8 a.m.-2:30 p.m., and an elementary schooler from 9:15-3:15 p.m. means that by the time all the kids are safely in class, the oldest child is ready to come home.

Until school and work schedules are perfectly aligned, some families are going to find those schedules problematic. Usually there are solutions to these problems, whether it is private childcare, before and afterschool care, or flexible work hours. The growing acceptability of working at home, chosen by many parents with the option to do so, is also giving many families more flexibility (according to the Pew Research Center, 35% of all workers offered the choice to work remotely full-time did so after the COVID-19 pandemic vs. only 7% pre-pandemic). Regardless, moving a middle or high school time to 8 a.m. or later is not the cause of problems balancing work and school, and, in fact, resolves as many problems as it may seem to cause.

In addition, it’s important to remember that we’re generally talking about starting middle and high schools later. The children concerned are 12 -18 years old, and usually do not need the same kind of parental supervision to get to school that younger children need. The fact that parents concerned about lack of supervision defend 7 a.m. start times, which go hand-in-hand with 2 p.m. dismissal times, or that they defend 7 a.m. start times for teenagers but accept 9:15 a.m. start times for first graders, suggests that the real concern isn’t childcare or work.

Even concerns about driving to work in rush hour are based on entirely unfounded speculation, not only because different families have different hours but because traffic patterns themselves are impacted not just by school hours but by complex adjustments communities make to them. In many communities it is the school buses themselves - and people driving their kids to school, in part to overcome early hours – that create the bulk of the traffic. If school hours shift, so will traffic patterns, so it's hard to say in advance just how any specific school start time relates to "rush hour." Predictions are especially challenging given that in many communities ridership on school buses is low for high schoolers who choose to drive themselves or their friends to avoid the early hours. It's entirely possible that when school hours are later, bus ridership wil increase, relieving a great deal of traffic. This is speculation, but so are fears about gridlock if schools change hours in any way.

SCHOOL STARTS ARE MORE THAN JUST ABOUT GOOD GRADES

In high performing school districts, administrators may wonder if it is worth making a change for a negligible improvement in grades. Students in early starting schools who have high GPAs may be achieving this by sacrificing their health. Their quality of life, including sleep deprivation, means that they are having more health problems for the sake of good grades.

There is also the pressure of rampant cheating that goes on in high performing school districts and high schoolers who are not measuring up may either cheat, induce self harm, or get a slew of health problems, including depression.

So, on the surface of a high performing high school, everything "looks fine" but often it is not. It's just too easy to see the good performance that masks everything else.

Unhealthy sleep, exacerbated by too-early school start times, is a public health issue. Even if delaying bell times had zero impact on grades, test scores, learning or school performance (which it does!), the improvement in health benefits, and proven reduction in behavior problems, risky behaviors, driving accidents and decrease in suicidal ideation, would be worth making the change.

Early bell schedules are not merely an academic performance issue. They are a public health issue.

In high performing school districts, administrators may wonder if it is worth making a change for a negligible improvement in grades. Students in early starting schools who have high GPAs may be achieving this by sacrificing their health. Their quality of life, including sleep deprivation, means that they are having more health problems for the sake of good grades.

There is also the pressure of rampant cheating that goes on in high performing school districts and high schoolers who are not measuring up may either cheat, induce self harm, or get a slew of health problems, including depression.

So, on the surface of a high performing high school, everything "looks fine" but often it is not. It's just too easy to see the good performance that masks everything else.

Unhealthy sleep, exacerbated by too-early school start times, is a public health issue. Even if delaying bell times had zero impact on grades, test scores, learning or school performance (which it does!), the improvement in health benefits, and proven reduction in behavior problems, risky behaviors, driving accidents and decrease in suicidal ideation, would be worth making the change.

Early bell schedules are not merely an academic performance issue. They are a public health issue.

COMMUNITY LIFE (INCLUDING CHILDCARE) ADJUSTS TO SCHOOL HOURS

When schools change schedules, so do schedules for other parts of community life--including childcare hours, afterschool programs, and even traffic patterns. So assuming that just because school starts or stops at a different time will destroy some current schedule is a mistake. In fact, we know that community life adjusts to school hours, whatever they are from thousands of schools that change bell times--which schools do frequently, earlier and later, for all sorts of reasons. We also have evidence from hundreds of districts that have delayed high school start times, as well as from even more districts that never moved so early, that things like childcare and practice times and after-school job hours all change to fit school hours by necessity. Sometimes they even change for the better when stakeholders come together to consider whether current childcare offerings or sports schedules are really ideal or even acceptable.

Fears that starting high school later might hurt working and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged families by taking out the teenage babysitter labor force, for example, are based on a slew of faulty assumptions and misconceptions about the relationship between school hours and community life, as well as a lack of evidence that this is a common pattern, a necessary one, or a desirable one. Consider the following:

When schools change schedules, so do schedules for other parts of community life--including childcare hours, afterschool programs, and even traffic patterns. So assuming that just because school starts or stops at a different time will destroy some current schedule is a mistake. In fact, we know that community life adjusts to school hours, whatever they are from thousands of schools that change bell times--which schools do frequently, earlier and later, for all sorts of reasons. We also have evidence from hundreds of districts that have delayed high school start times, as well as from even more districts that never moved so early, that things like childcare and practice times and after-school job hours all change to fit school hours by necessity. Sometimes they even change for the better when stakeholders come together to consider whether current childcare offerings or sports schedules are really ideal or even acceptable.

Fears that starting high school later might hurt working and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged families by taking out the teenage babysitter labor force, for example, are based on a slew of faulty assumptions and misconceptions about the relationship between school hours and community life, as well as a lack of evidence that this is a common pattern, a necessary one, or a desirable one. Consider the following:

- Quite often people make this claim that families rely on teenagers to watch younger kids without a lot of evidence that this is a major trend in the community—or without considering that this may be what some families do but isn’t the only way to handle childcare. In fact, given that right now no school hours match all parental (or, really, any parental) work hours, these adjustments are already being made—we just don’t notice what we do right now as much as we worry about what MIGHT happen if we change things.

- Fortunately, experience in hundreds of districts that have delayed high school start times—as well as from many more districts that never moved secondary schools so early—inevitably shows that community life adjusts to school hours, not vice versa. When school hours local parks and recreation services, school-based care, and private daycares swoop in to fill the gap.

- Remember, too, that right now the same families relying on teenagers to care for children after school right now are often struggling to find childcare BEFORE school.

- The argument that that many families rely on teenagers fails to consider what these families did when those same teenagers were their oldest children. Clearly there are many family structures, work schedules, and needs. That is not a sufficient reason to deprive an entire teenage population of sleep.

- Consider that the same families who count on teenagers after school to watch their kids have to find some other form of childcare BEFORE school—because quite often elementary schools start at 9 a.m. or even later. If high schools suddenly took the 9 a.m. slot, the problem might be flipped to after-school care, but ultimately families are forced are one time or another to find some form of childcare other than teenagers.

- Consider also that children from poor, minority, and otherwise socioeconomically disadvantaged families already suffer disproportionately from inadequate sleep and that moving to later middle and high school start times disproportionately BENEFITS middle and high school students from these same families.

- Teenagers are still growing and developing, too, and it is irresponsible for communities to give them work responsibilities that threaten their health, safety, and well-being.

SCHOOL START TIMES ARE A SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSUE

Decades of evidence shows that the status quo of early secondary school start times hurts underprivileged kids the most. In fact, we now know that early school start times are a social justice issue: not only do students from socioeconomocially disadvantaged groups and minorities experience disproportionately greater sleep challenges, but appropriate school start times are proven to narrow achievement gaps and health disparities. Under the status quo, for example, disadvantaged teens often have long walks or bus rides to school, so they have to get up even earlier than their more privileged peers, and if they arrive late they may miss their school-provided breakfast. Immigrant families are less likely to get the 8-5 white collar schedule, and are more likely to have to work very early shifts, swing shifts, or very late shifts. A child from a disadvantaged family who misses the bus may have no way to get to school at all and end up with a tardy or truancy record, whereas a more privileged child may have their own car, a ride to school, parents who know how to write penalty-free "excuses" for tardies and absences. More affluent children also have the option of getting professional help for sleep issues and related psychological or health problems, as well as better options to attend alternative schools with healthier hours.

None of this is to say that many families, including most in the United States, face serious challenges, or that changing school start times might not present unique challenges to underprivileged children and families. But here it's important to remember that these same children and families are being harmed right now by doing nothing. Just because adjustments need to be made is not an excuse to continue doing damage, nor is it an excuse to deprive an entire population of sleep. The only rational and proven way to determine school start times is to do what is best for kids, and there is absolutely no question that starting school later is best for kids, especially the most underprivileged kids we are rightly concerned about.

Decades of evidence shows that the status quo of early secondary school start times hurts underprivileged kids the most. In fact, we now know that early school start times are a social justice issue: not only do students from socioeconomocially disadvantaged groups and minorities experience disproportionately greater sleep challenges, but appropriate school start times are proven to narrow achievement gaps and health disparities. Under the status quo, for example, disadvantaged teens often have long walks or bus rides to school, so they have to get up even earlier than their more privileged peers, and if they arrive late they may miss their school-provided breakfast. Immigrant families are less likely to get the 8-5 white collar schedule, and are more likely to have to work very early shifts, swing shifts, or very late shifts. A child from a disadvantaged family who misses the bus may have no way to get to school at all and end up with a tardy or truancy record, whereas a more privileged child may have their own car, a ride to school, parents who know how to write penalty-free "excuses" for tardies and absences. More affluent children also have the option of getting professional help for sleep issues and related psychological or health problems, as well as better options to attend alternative schools with healthier hours.

None of this is to say that many families, including most in the United States, face serious challenges, or that changing school start times might not present unique challenges to underprivileged children and families. But here it's important to remember that these same children and families are being harmed right now by doing nothing. Just because adjustments need to be made is not an excuse to continue doing damage, nor is it an excuse to deprive an entire population of sleep. The only rational and proven way to determine school start times is to do what is best for kids, and there is absolutely no question that starting school later is best for kids, especially the most underprivileged kids we are rightly concerned about.

IS THERE A LIST OF HOW MANY SCHOOL DISTRICTS HAVE CHANGED START TIMES?

Data collection of school start times is not a simple issue. We delve deeper into the challenges of this question here.

Data collection of school start times is not a simple issue. We delve deeper into the challenges of this question here.