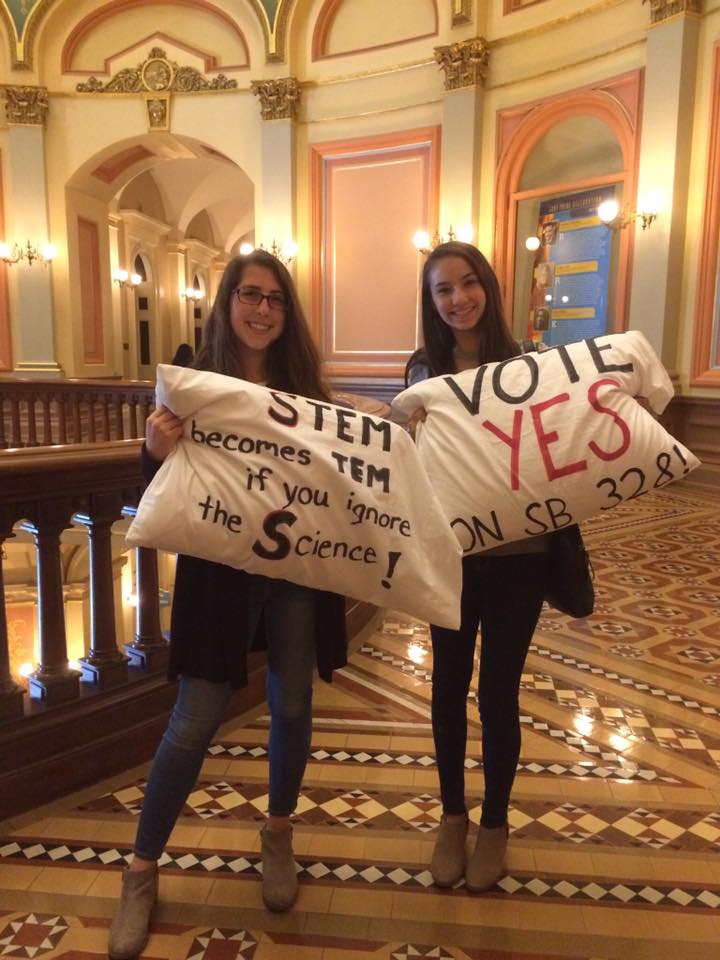

by Lisa Lewis The issue of school start times first hit my radar in the fall of 2015, when my son entered high school. In our community, high school started at 7:30 a.m. But why? Was this the norm elsewhere, too? As a parent and a journalist, I started gathering information and writing about the topic. I also reached out to our district superintendent but got zero response. In the fall of 2016, I wrote about it again, for the Los Angeles Times. While the op-ed gave me a boost of local visibility, there wasn’t any immediate change. Having recently started up a local chapter of Start School Later after connecting with the group during my research, I shifted my focus to seeing what I could accomplish locally. Then, in January 2017, I found out my op-ed had sparked something bigger. State Senator Anthony Portantino, whose district is in Los Angeles, had read it. As it so happened, his daughter’s high school was in the midst of discussing later start times, so it was a topic that resonated with him. He looked into the issue further and decided to introduce a state bill. His office reached out to Start School Later, which agreed to sponsor the bill and looped in the state’s chapter leaders. That bill, SB 328, which proposed 8:30 a.m. as the earliest allowed start time for the state’s middle and high schools, was introduced in February 2017. There had been similar proposed legislation in other states, but nothing of this scope had ever succeeded. Almost immediately, the immensely powerful California Teachers Association, along with the California School Boards Association, decried the bill as overreach that impinged on local control. Meanwhile, the California Parent Teachers Association, focused on the bill’s merits for kids’ well-being, announced its support. The PTA provided key input that helped shape the bill, including having a three-year window to allow enough preparation, as well as clarifying that “zero periods” (optional before-school classes) could still be offered. Drawing on the experience and guidance from Start School Later, several of us in California formed a virtual team: Mariah Baughn and Beth McNeill in San Diego, me in the Los Angeles area, Irena Keller (who’d founded the statewide Start School Later chapter) in the San Francisco Bay Area, and Joy Wake, Sue Gylling and Anne Del Core in Sacramento. Another key player: Stanford sleep specialist Rafael Pelayo, who serves on Start School Later’s Board of Directors. Among our strategies:

Over a two-year period, the bill made it through numerous committees as well as floor votes on both the senate and assembly sides, eventually reaching Gov. Jerry Brown’s desk. All that was needed was his signature. Instead, he vetoed the bill, stating that he believed the decision should be made locally. Luckily, 2019 brought a new governor and another chance. On Feb. 15, 2019. Sen. Portantino brought the bill forth again, with two key amendments: an exemption for the state’s rural districts, and a start-time change for middle schools to “8 a.m. or later” rather than the “8:30 a.m. or later” change for high schools, which provided additional flexibility. This time around, the California PTA signed on as a cosponsor of the bill, which brought additional visibility and resources. Again, the bill made it through all of the previous steps. Gov. Gavin Newsom had thirty days to sign it into law – or veto it, as his predecessor had. There was a final blitz of letters to Newsom’s office. There were final appeals from supporters. And, we knew, there were similar activities opposing the bill underway. Finally, at about 8:30 p.m. on the very last day, Newsom signed it into law. What it finally took: Persistence, allies, communication, timing, flexibility This included:

Ultimately, what we accomplished in California drew on the body of research and many advocacy efforts to date, as well as the active support of countless researchers and the critical connections forged by Start School Later. May it continue to bolster similar efforts elsewhere. Adapted excerpt from The Sleep-Deprived Teen: Why Our Teens Are So Tired, And How Parents And Schools Can Help them Thrive, published by Mango Publishing Group, June 2022. Lisa L. Lewis is the author of The Sleep-Deprived Teen: Why Our Teenagers Are So Tired, And How Parents And Schools Can Help Them Thrive, described as “a call to action” by Arianna Huffington and “an urgent and timely read” by Daniel H. Pink. The book is an outgrowth of her previous work on the topic, including her role helping get California’s landmark law on healthy school start times passed. Lewis has written for The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Atlantic, and others. She’s a parent to a teen and a recent teen and lives in California. More info: www.lisallewis.com.

0 Comments

An up-to-date, peer-reviewed summary of the research on teen sleep and school start times--plus expert recommendations about ways to build on that research and turn it into school policy. By Elinore Boeke We’re excited to share a newly-published summary of last year’s Summit on Adolescent Sleep and School Start Times: Setting the Research Agenda for California and Beyond. The Summit was spearheaded by Start School Later/Healthy Hours, and hosted by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine with support from the National Sleep Foundation and American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The peer-reviewed summary is now available online, and will be included in the February 2022 print edition of the Sleep Health Journal, published by the National Sleep Foundation. Using an extensive body of multidisciplinary research, the Summit established once and for all that most US schools should—and can—start later in the morning. It also identified ways future research questions might help turn this research into school policy — including ways to build community support for and awareness of healthy sleep while reducing disparities. PLEASE WIDELY SHARE THIS TERRIFIC SUMMARY OF THE EVIDENCE SUPPORTING HEALTHY SCHOOL START TIMES! We’ve created the shareable graphics you see in this blog with quotes from the paper for your use. (If we missed a useful quote, or if you need a different size, please reach out to Elinore Boeke, SSL communication director, at [email protected]. BACKGROUND The impetus for the Summit was California’s SB328. Passed and signed into law in 2019, this is the first U.S. statewide legislation ("healthy school start time" law) explicitly designed to protect adolescent sleep health by requiring most California public school districts to start no earlier than 8:00 a.m. for middle schools and 8:30 a.m. for high schools. The bill was co-sponsored by Start School Later and the California State PTA. California schools must implement the new law in place by July 1, 2022, or by the expiration date of any district or charter school’s bargaining agreement in effect on Jan. 1, 2020 Recognizing the unique opportunity presented by the the groundbreaking new law’s three-year implementation period, Start School Later brought together participants from a wide-range of academic backgrounds who organized a virtual summit to review current knowledge on adolescent sleep health and school start times and provide key research recommendations. The summit’s conclusions support the National Sleep Foundation’s new position statement recommending that middle and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. and calling on the federal government to provide and fund evidence-based resources and monitoring to help school communities delay bell times and reduce sleep health disparities associated with school start times. Terra Ziporyn, PhD (aka Terra Ziporyn Snider), Executive Director and Co-Founder of Start School Later, is the lead author of the paper. Other members of the Start School Later Board of Directors, Advisory Board, and National Team are also authors on the paper: Judith Owens, MD; Amy Wolfson, PhD; Rafael Pelayo, MD; and Phyllis Payne, MPH. We encourage you to share this paper with school leadership, elected officials, community leaders, and others with an interest in improving student outcomes. MORE SHAREABLE IMAGES

Battling over sleep with your teenager? It doesn't have to be that way. By Stacy Simera, MSSA, LISW-S  As a therapist and a mother of two recent teens, I know that there are a lot of areas of conflict that can arise between parents and their children, including homework, screen time, chores, clothing, and money. When it comes to bedtimes and sleep, we parents are often too tired to fight–literally and figuratively. Yet research from the last few decades is telling us that enforcing healthy sleep patterns is a battle well-fought. Chronic deficient sleep is tied to increased risk of teen car crashes, diabetes, depression, suicide, cardiovascular disease, immune dysfunction, and more. Every animal on this planet needs sleep, and you will have a healthier and happier teen if you help ensure they get around 9 hours of sleep each night. But don’t look at it as a battle between you and your teen. Instead, view it as a team effort in which you and your child are fighting against societal norms and lack of awareness. Your teen has heard adults say things like “The early bird gets the worm,” and they’ve seen influential people brag on social media about how little sleep they get while they are making buckets of money or important decisions. Your teen may also have a school schedule that is unsupportive of sleep – with bus pick-ups at 6 a.m. and sporting events that run late on school nights. Yet data shows that persons in the highest income brackets get more sleep than persons in poverty, and humans make our best decisions when we get adequate sleep. And local educational institutions were, ironically, not well-educated on sleep when they set up their schedules–schedules that are based on convenience, not on student biology. But the aforementioned influences most likely have led your child to underestimate the vital importance of sleep on human physical and psychological well-being–and we need to change that. Here are my tips for having a healthier and happier teen: Educate on the benefits of good sleep, rather than the risks of poor sleep. Education can go a long way in improving health behavior. But keep in mind that adolescents tend to pay more attention to benefits rather than risk. Part of this is related to how their brains process information, and part of this is related to their sense of invincibility. Telling a teen that lack of sleep has been associated with increased risk of sports injuries won’t be as effective as telling them that improved sleep has been shown to increase athletic performance and recovery. (Just look at some of the classic studies at Stanford on sleep and athletic performance, including improved free-throw percentages among basketball players.) You know what will best influence your child, so look through some of the data on this website and find out which of the many benefits of sleep will resonate with your teen, whether it is improved mood, memory, weight management, academic performance, or skin health. Telling a teen that lack of sleep has been associated with increased risk of sports injuries won’t be as effective as telling them that improved sleep has been shown to increase athletic performance and recovery. Acknowledge the later shift in sleep cycle, but don’t let it be an excuse for 2 a.m. bedtimes. Your teen may be aware of the phase delay that occurs during puberty, and they may therefore cite that delay as a reason why they can’t adhere to an early bedtime. While the science is clear on the changes in sleep during puberty, don’t let that be an excuse for obnoxiously late bedtimes. I’ve had these discussions in therapy sessions, and they often go like this: Me: How much sleep are you getting lately? Teen: I dunno, maybe four or five hours. Me: Why only four or five hours? Teen: Well, I have to get up at 6 a.m. to catch the bus. Like you’ve said, school should start later. [Kids often Google me and find out that I volunteer for the non-profit Start School Later.] Me: Yes, school should start later, but that’s not the only problem I see. If I’m doing the math right, on nights that you get four hours of sleep, you’re going to bed at 2 a.m., right? Teen: Yeah, because of that later shift in sleep. It’s biology. Me: Okay… I’m glad you’re listening to science, but that’s not exactly how it works. Yes, you’re on a later shift in sleep during puberty, but that shift is around one to two hours later, not four hours later. I have no problem telling your parents that an 8 or 9 p.m. bedtime is unrealistic, but 2 a.m. is not biology, that’s you staying up too late. Which leads us to the next tip… Be vigilant about screen time and caffeine use. If you first acknowledge the later shift in sleep cycle, your teen may not resist the next conversation – which is about screen time and caffeine use. Sure, you aren’t expecting your teen to go to bed at the same time as their eight-year-old sibling, but you also don’t want your teen to sabotage their chances for a decent bedtime. You and your teen are probably aware of the negative impacts of caffeine and screen time on sleep - but awareness and vigilance are not the same thing. Caffeine Awareness Encourage your teen to read labels or search online for the caffeine content of items that are popular amongst their peer groups or teammates. People are often stunned to find out how much caffeine is in certain products, including athletic drinks or mixes (especially “pre-workout”) and chocolate (sorry to break that news). Your teen may insist that caffeine doesn’t impact them, but it will, especially within six hours of bedtime. Blue Light Filters I’d like to tell you to limit screen time in the evening, but I’m well-aware that evening screentime is inevitable, including for us adults. Therefore, another option is to enable a blue light filter on the various devices in your home or wear blue light filter glasses. Most newer phones, tablets, and laptops have an option in the settings, sometimes called “Night Mode,” that will filter out the stimulating blue light every evening and change the screen output to an orangish hue. Your teen has to turn this option on, and I highly encourage that you not only ask them to do it, but also follow up and make sure they did. If they have older devices, there are apps they can download. Enacting a blue light filter doesn’t mean that you can have your nose in your tablet without negative impact, but it’s better than nothing. You can’t pour from an empty pitcher. It’s the same for parents, so take care of yourself as well. Advocate for healthy school start times–districts are often influenced by parents more than data. Nearly every major medical group in the country has very clearly stated that middle and high schools should start after 8:30 a.m., and even the RAND Corporation crunched the numbers and showed that there is a positive economic impact when schools start later. Yet research and data and medical position statements don’t influence local school districts as much as parents do. Parents pay the taxes and vote in the school board members (in most districts) and fill the seats at band concerts and soccer games. Talk to your school board and your superintendent, get your PTA involved, and make it clear that the parents are asking for, and support, a move in the right direction. Fight for your teen when needed. Your child has no greater champion than you, and sometimes you have to fight for your child. If the cause of your child’s poor sleep is related to sports schedules, talk to the coach about those late-night practices. Maybe you’re the fourth parent to say something, and the coach is now motivated to make adjustments. Research and data and medical position statements don’t influence local school districts as much as parents do. If your school is resistant to adopting healthy school start times, and you know your child is suffering, explore creative options. In middle school, I allowed my sons to periodically sleep in on Wednesdays, especially during sports seasons. When my oldest was in high school, I asked for study hall first period and he skipped it every day (my youngest chose a STEM high school that started an hour later than the local public school). I am aware, however, that my children benefited from my ability to drive my children to school, and I know that not every household has that flexibility. If your child’s sleep continues to be deficient or disrupted, and you can’t figure out why, talk to your primary care physician and see if a referral is needed for a sleep study or mental health assessment. Depression, anxiety, and PTSD can greatly interfere with sleep, as can many sleep disorders. Get good sleep yourself. My last tip is for you to get good sleep yourself. Adults should get around 8 hours of sleep, and when you get the sleep you need, you’ll have more energy for effective parenting. There’s a saying among mental health professionals: You can’t pour from an empty pitcher. It’s the same for parents, so take care of yourself as well. Stacy is an independently-licensed social worker. She provides therapy for children, adolescents, and adults at Kent Psychological Associates and serves as the chair of the sleep committee for the Ohio Adolescent Health Partnership.

Many school districts may need statewide legislation to spur or support later start times. Here's what you can do to help that happen. by Terra Ziporyn Snider, PhD Has your district still failed to ensure safe, healthy school hours? Join the club. Though any school district can establish sleep-friendly school hours on its own initiative--and many have--most still have not taken action. Despite clear calls for change since the 1990s, many school districts may need statewide legislation to spur or support later start times. Below are some advocacy tips that we've picked up over the years working for bills to study, incentivize, and even mandate sleep-friendly school start times. You can also find information on current legislative activity—as well as past success stories—on Start School Later's Legislation Page. Tip #1: Find an elected official to champion the cause To get your bill off the ground, you first want to find an elected official to introducing, or sponsoring, it. A bill can have numerous sponsors, often referred to as co-sponsors, but someone needs to get the ball rolling. Tip #2: Start with your own elected official(s) If that person or delegation won’t take the lead, it’s wise to pursue a legislator or several who serve on or lead committees that have the authority to work on health, educational or appropriations-related legislation Despite clear calls for change since the 1990s, many school districts may need statewide legislation to spur or support later start times. Tip #3: Determine if you or the legislator is taking the lead Some legislators will do the needed research and bill writing. Others will rely on you or other advocates to provide information, do research, and even draft bill language. Tip #4: Connect with Start School Later Ideally you should choose 1-2 representatives from your state or local Start School Later chapter who have the knowledge and time to be a resource and partner. The legislator can use Start School Later in getting support from both constituents and expert organizations likely to support the bill, Tip #5: Strive for bipartisan support Try to find legislative sponsors and subsequent "yes" votes in both legislative chambers (when there are two) and within both or all political parties, Emphasizing that it's much easier for local leaders to do the right thing (and deflecting community ire away from local school leaders) can be key. So can emphasizing that statewide parameters ensure that child's ability to go to school at sleep-friendly hours won't vary by zip code Tip #6: Neutralize the opposition

While advocates for healthy school hours see starting school later as a no-brainer, many people don’t. Any legislative effort for school hours change will attract the attention of individuals and organizations—including parents, teachers, school officials staff, and local businesses--that fear and thus oppose change. Some of these opponents have the type of financial resources and influence that community advocates just don't have, so it is important to find ways to neutralize their opposition. Try talking and compromising with them, using evidence to counter speculation and fear, or, if all else fails, minimizing publicity about the legislation until absolutely necessary, Tip #7: Build a base of supporters As an advocacy leader, you want to establishing an energized and committed base of supporters in place before introducing legislation. You need to be able to ask these supporters to supply written and oral testimony at legislative hearings and to contact legislators during key votes, sometimes with a very quick turnaround. An email list of people who support healthy teen sleep and sensible school start times can be invaluable here. Such supporters should be asked to take action by, for instance, signing an online petition; calling, writing to or visiting the offices of their legislators; writing letters to newspapers, posting on social media, and/or influencing others. Tip #8: Stress that local districts need help--and that they CAN make this work Stressing the need for help ensuring safe, healthy, equitable school hours—and the feasibility of doing so—is critical. Even if legislators agree that school should start at 8:30 or later, they will often reject legislation on the grounds that school hours should be decided locally ("local control") or that change isn't practical and/or affordable. That leads to a lot of agreeing that this "should be done" but also a lot of "kicking the can." Emphasizing that it's much easier for local leaders to do the right thing (and deflecting community ire away from local school leaders) can be key. So can emphasizing that statewide parameters ensure that child's ability to go to school at sleep-friendly hours won't vary by zip code Note: This blog was adapted from Start School Later materials originally put together by Debbie O. Moore Terra Ziporyn Snider, PhD, is the Executive Director and Co-Founder of Start School Later/Healthy Hours. What if this pandemic is not a disaster for students but an opportunity to learn more in a better (and healthier) way? by Roger Pinholster and Kimberly Damron The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed our lives in unanticipated ways. We have had to learn to value workers who are often taken for granted, change the way we relate to others, and rely on technology to function and maintain connection in our lives more than ever. As part of this change, we have also had to quickly adapt to a new way of educating our children and develop a new appreciation for teachers and the vital role they play in learning. This fall the country will almost certainly open up and expect students to return to school. At the same time, parents, schools, and communities can anticipate:

New Ways to Teach, Learn, and Schedule Schools We need to see this not as a disaster for students, but as an opportunity for students to learn more in a better way. This will be a chance to change our approach to teaching and learning as well as how school is scheduled. Schools are already planning BUT -- WHAT IF...

Students with disabilities requiring more structure might come to brick and mortar schools four days a week and stay home on Fridays to learn online since their class sizes leave room for distancing now, especially if we have some empty regular classrooms. Imagine the attention each student could get, the individual feedback on problems/labs, the chance to safely ask questions, the higher order discussions you could have, and the amazing learning that could happen. Teachers might be assigned a slightly larger number of students and class sizes but close to the same, maybe 10 percent more to save teacher units for a different team member. Except, instead of 22-28 students seated in the class at one time, the teachers could work with 11 to 14 students live and in person (instruction wouldn't change until you got below 15 according to research). Imagine the attention each student could get, the individual feedback on problems/labs, the chance to safely ask questions, the higher-order discussions you could have, and the amazing learning that could happen. A Co-Teaching Model The academic teachers’ total class sizes might be a little larger because some current teachers would need to evolve into a different way of teaching and learning because they are at risk. Maybe 10-15 percent of current classroom teachers and staff might be too vulnerable to teach students live in the classroom until there is a vaccine in a couple of years. Possibilities could be that they are over 60 years living, are youthful but have underlying health issues, have already worked as teachers in the virtual arena, etc. These teachers, non-classroom teachers, and volunteer retired teachers would become co-teachers. They would share students with the teachers that are providing direct instruction in the classroom. Schools might need to exchange teachers for a year to match needed certifications. They could be trained this summer to teach and manage the virtual and online learning tools for their assigned grades and or subjects. An advantage would be that some will have already been doing this work for a semester and will have familiarity with it. They might work from home four days per week and come to school on Friday for a half day to coordinate at a safe distance with their teams and partner teachers--no faculty meetings allowed (smile). If more frequent coordination is needed, meetings could be done virtually from home (as is being done now for so many teams). On-line teachers might also teach from school in special areas of safety that can be established at the actual school locations. Combined Classroom and Distance Learning Three days a week students would be at home or at very small community centers involved in distance learning. School technology folks would be needed to support the co-teachers and their teams to manage this learning and keep students on track. One co-teacher might manage 100 elementary students or 160 secondary students and then coordinate with four classroom teachers in a grade or secondary subject. On the Friday assessment day, they would determine student progress and adjust the student’s individual curriculum with the classroom teacher. Together they would produce a two-week progress report for students, parents, other teachers of the student, and administrators. Students could even be involved in this process virtually as appropriate. A Trauma-Informed Approach to Discipline This might be a great time to transition to trauma informed interventions. With 12-14 in a class and no cafeteria lunches, it may be possible to have fewer Assistant Principals and Deans actually at school…and even school resource officers. Let those specially trained staff be focused on building resilience in target communities they share and problem solving with kids and families. School counselors would not want to pull students during the two in-school days so they might team with social workers, psychologists and contracted mental health folks to play an integral part of this trauma-informed team and provide interventions for students and parents out in the community. These workers would need extra protection--flu shots, virus testing--in order to keep safe and could use telehealth services where appropriate and able. Hot lines and call centers could also be used as needed. Using Space, Time, and Staff More Efficiently Cafeterias and auditoriums might hold 40-75 or so students for their distance/virtual learning days who can’t initially find computers, have just moved here, or have daycare issues. Current paraprofessionals might support these students. Students could go to the media center or the school-based labs we have set up now in schools. Schools might not need as many bus drivers with fewer routes, and fewer school cafeteria workers would be needed as well. As is being done during the pandemic, school systems might employ those qualified workers to support lunch for disadvantaged students at home and in the small community centers. The community feeding program and the regular driving and feeding assignments could be a team effort, rotated among the staff team. Grub hub for kids! Students could also take breakfast items home in their backpacks the days they come to school. On Fridays staff could assess, plan together, and clean. No students at school, but they are available on-line to participate in the assessments as appropriate. Staff might deep clean and disinfect without students there. Students would all be home on Friday. They could take online assessments, do project assessments at home, write essays/stories/articles requiring higher levels of thinking, watch a video together and analyze in a chatroom, do labs--real and virtual. On Fridays, teachers and co-teachers could work till midday at school with no students and have long weekends. They might work the same hours per week as in past years because the other four days would be extended about 50 minutes. Personal, Flexible Schedules--and More Sleep! In all, you would be able to use the same staff and resources. It could be a scheduling nightmare, as the saying goes, for secondary schools. Teachers might teach six periods and have one period plan for the four days per week. This would mean academic-subject-area teachers would teach more sections, which would be needed in order to free up more co-teachers. A possible solution might be for students to have study halls in media centers and labs in order to make the schedule work so teachers could have a planning period each day. Total planning time might increase slightly with the Friday assessment day. These issues could be addressed by each school to develop the best way to support the teachers in this process. The community feeding program and the regular driving and feeding assignments could be a team effort, rotated among the staff team. Grub hub for kids! For students these changes would be a blessing in some ways. They could get adequate sleep a few more days a week. Secondary students would only be committed to a certain school time schedule of 18 hours per week for the two days they are at school versus the 40 hours per week they have to commit to now, which includes bus rides, lunch shifts, pass time, etc. Most of the online/virtual learning could be done on their schedule except for certain lessons. For secondary students this would leave them a way to build a more relaxed and flexible personal schedule that would allow them to safely:

Childcare and Other Challenges Lots of roadblocks and challenges will be associated with this approach. Like...what to do with the extra furniture...maybe send some home? Seriously, safe daycare will be one of the main issues to be solved. Parents are currently providing supervision and coaching now because they are sheltered with their kids. When they go back to work who will supervise and coach? Secondary students may drop out to take care of their siblings. Students may experience stress-related mental health problems that go unnoticed. Childcare has to be a priority before this approach can be considered. Staffed community centers and places of worship in at-risk neighborhoods will become vitally important to support kids and families where there are limited resources and support. A solution will need to be developed through a collaborative effort between schools, families and each unique community and not left up to the parents to struggle alone in finding child care. Students can get adequate sleep a few more days a week. Secondary students will only be committed to a certain school time schedule of 18 hours per week for the two days they are at school versus the 40 hours per week they have to commit to now, which includes bus rides, lunch shifts, pass time, etc. Another consideration might be to develop a year-round school schedule that does not leave a huge gap over the summer for families, requiring readjustments once routines have been established. This would also allow for a less pressured school year and for numerous week-long breaks and recovery for kids, parents, and teachers. Additionally, with fewer pressures to complete work before the summer break, more flexibility can be incorporated in adjusting the schedule to unexpected occurrences such as natural disasters, epidemics, etc. Bridging the Digital Divide The community has to work together to bridge the digital divide. Finding computers and providing internet access to perhaps a third of their students who have none will take not only the school system but other government entities, businesses, foundations, and other community organizations to fund and deploy what is needed. Overall health, well-being and mental health for everyone will be prioritized with a more relaxed schedule. School systems should have a resource in their Title I funds that come each year from the Federal Government. Typically, a large percentage of these funds are used to hire extra teachers to reduce class size for disadvantaged students.

With the new class size at 14 these funds can be redirected to provide students with laptops and Wi-Fi. For example, the Leon County Florida School District has implemented the “Smart Bus Initiative,” which strives to “bridge the digital divide” by providing Wi-Fi to neighborhoods that may not have easy access to connectivity. Putting Health and Safety First Everyone--students, teachers, staff, volunteers, etc.--would need their temperature taken and informal checks/interviews before class starts. All school personnel/volunteers should have COVID-19 testing once per month and all students once a semester. Appropriate social distancing measures should be in place, and everyone will need to have PPE, but that can be stylish (smile). Overall health, well-being and mental health for everyone will be prioritized with a more relaxed schedule. Implementing this approach to teaching and learning will be a challenge for sure, but it might also be a better way to teach and learn within the constraints schools and communities will face in the fall and future. We may only have to adjust for a year or until a viable vaccine is in place, but developing a sustainable way of teaching and learning through whatever we may face together is worth exploring. Wanted: More Creative Solutions Change is difficult. Even so, it has become clear that we are capable of adapting when necessary. Crises produce opportunities and we have been given a golden opportunity to evolve in the way we approach learning. Please send us your creative solutions for the fall. We will compile and distribute them on various platforms and organizations to keep the discussion going. Roger Pinholster has worked in schools for 40 years as a teacher, counselor, principal, district administrator, and consultant. ([email protected]). Kimberly Damron has worked as a Licensed Mental Health Therapist for 13 years focusing her practice on children and family issues and is a child/family/community advocate and parent of a 16-year-old son. ([email protected]). This groundbreaking law affirms the moral imperative for states to step in when local communities cannot protect children’s safety, health, and basic rights. by Terra Ziporyn Snider In 2012 I wrote a commentary in Education Week (Push Back High School Start Times) arguing that ensuring safe, healthy school start times requires recognizing sleep and school hours as public health issues. Even back then the science was clear: requiring adolescents to be in class too early in the morning is unhealthy, unsafe, and counterproductive. The problem districts had ensuring healthy bell times wasn’t the science: it was the politics. Since then, there has been increasing recognition both about the strength of the science and the problems of leaving public health matters in the hands of individual school districts, culminating in California’s new “start school later” law. This law, which requires most state middle and high schools to adopt minimum opening times (8 a.m. for middle schools, 8:30 a.m. for high schools), is based on an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement recommending that middle and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to allow growing brains and bodies an opportunity to get enough sleep at the times they most need it. Many other health and education organizations—including the American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Society for Behavioral Medicine, National PTA, and National Education Association—have subsequently issued or endorsed the same recommendation. As Settled As Science Gets Despite some media claims to the contrary, the science grounding this law is as settled as science gets. A large, broad, and consistent body of evidence shows that most adolescents cannot get healthy sleep if they are forced to be in school too early in the morning—and that returning to developmentally appropriate bell times is a proven countermeasure to adolescent sleep deficiency. California’s Governor Newsom has provided a wise and courageous solution to this decades-long impasse by setting minimum standards for how early schools can start classes, finally stopping the process of passing the buck for a practice causing serious and unnecessary harm. Organizations such as the AAP and AMA do not issue policy statements lightly, and their recommendations are a testament to the strength of this research. In fact, in response to legislative analysis casting doubt on the strength of the science, over 120 research, health, and public policy experts immediately signed a consensus letter confirming that the "volume, breadth, consistency and strength of the peer-reviewed scientific research supporting this legislation are unequivocal, and they exceed the high standards for public health and education policy." Last October a Pennsylvania Joint State Government Commission Report reached similar conclusions, stating that their recommendation for secondary schools to start at 8:30 a.m. or later “is also that of medical organizations and supported by scientific evidence.” The report adds that evidence from districts in Pennsylvania and around the nation that have successfully delayed bell times obviates the need for a pilot proof-of-concept program. In addition, it provides specific, evidence-based guidance to help communities use the opportunity provided by developmentally appropriate bell times most effectively. These change-management practices include providing sleep education in school health curricula, raising awareness about the benefits of later start times, and engaging authentically with community stakeholders. Costs of Inertia Much of the media coverage of California’s new law highlights speculation about ways in which changing bell times might be “disruptive” to districts and communities. Such speculation misses the point that such disruption—even if and when it occurs—is often overestimated, temporary at worst, and ultimately minor compared to the benefits received. Speculations about what “might” happen if bell times change also overlook the very real costs of not changing. Yes, all change comes with challenges and even costs, but the clear lesson from the many communities that have delayed bell times successfully is that when there's political will to change, stakeholders can and do collaborate iteratively to find creative solutions to both perceived and real logistical challenges. When school leaders embrace change and work with community stakeholders to develop a culture of healthy sleep, the benefits from later school start times are even greater. Speculations about what “might” happen if bell times change also overlook the very real costs of not changing. Human nature makes us all unconsciously value the way we do things now over the value of change (“status quo bias”). It also makes us discount or overlook existing problems that come from inaction compared to problems that might come from taking action (“omission bias”). Thus, when we talk about later start times possibly “not working” we forget what’s not working right now. Our tendency to overestimate costs of change while overlooking the costs of not changing helps explain why most districts have struggled to turn established science into school policy. We forget the many children and families whose mental and physical health, safety, and school performance are suffering because we force growing children to deprive themselves of sleep to attend class. We forget the challenges to working families with current school hours, which often differ drastically from elementary to middle to high school—and that often change as children move through the school system. We forget that school start times were set, and continue to be set, for all kinds of reasons, but convenience of families and even school employees was never one of them. We also forget that since work and school hours are not coordinated, and that for every family that likes current hours is another struggling with them. We forget that school start times were set, and continue to be set, for all kinds of reasons, but convenience of families and even school employees was never one of them.

Empowering School Districts California’s Governor Newsom has provided a wise and courageous solution to this decades-long impasse by setting minimum standards for how early schools can start classes, finally stopping the process of passing the buck for a practice causing serious and unnecessary harm. This groundbreaking law also changes the landscape for communities across the nation grappling with similar challenges by establishing the moral imperative of states to step in when local communities cannot protect children’s safety, health, and basic rights. By removing the greatest roadblock to change—the fear of community pushback and political repercussions of that pushback—California’s new law empowers local districts to prioritize student health and safety when they set schedules. The hope now is that instead of speculating about what might go wrong, districts use the many experience-based resources available to them to take advantage of this opportunity to address a profound and unnecessary harm. How to put parenting skills to work for children’s health and safety. by Debbie Owensby Moore  Debbie Owensby Moore, leader of Start School Later Texas and Start School Later's former national chapter director. Debbie Owensby Moore, leader of Start School Later Texas and Start School Later's former national chapter director. I recently read Shannon Watts book Fight Like a Mother. Watts founded the Moms Demand Action national advocacy group. As as Start School Later advocate for seven years, I quickly discovered how well the book provided wisdom and encouragement for mom advocates. Advocates all have a story or defining moment that propelled us into action. Like most, my Start School Later advocacy began when my child entered high school. And like many, I questioned if I was the right person to lead a local chapter. Who was I? Nothing but "just a mom". I was angered as the school district described our local efforts as two disgruntled loud-mouthed moms. But after reading this book, I realize that label is one I should embrace. There is a saying that if you want to ensure something gets done, just ask a busy mom to do it. Moms are the perfect advocates for children’s health and safety. Parenting requires empathy, compromise and common sense all while instilling values. We know how to multi-task and learn as we go. We get things done. There is a saying that if you want to insure something gets done, just ask a busy mom. Moms are motivated by our love of children, not power. And we are experts on issues affecting children and families, regardless of our education or training. As moms, we are often friends with other moms because our children share a common activity. Or maybe we are neighbors or co-workers. But working with folks who share similar values provides a deep connection. A sense of empowerment begins to take the place of our self-doubt. It didn’t take long after becoming involved with Start School Later that I realized advocating for children health and safety provided a connection that I had not experienced before. ...as our knowledge into the research grows, we become experts on adolescent sleep in our own right, regardless of our background. That knowledge propels one to grow personally as a public speaker whether addressing a school board, speaking to the media, or providing legislative testimony. Many SSL chapter leaders are introverts, myself included. But as our knowledge into the research grows, we become experts on adolescent sleep in our own right, regardless of our background. That knowledge propels one to grow personally as a public speaker whether addressing a school board, speaking to the media, or providing legislative testimony. In my previous role as the SSL national chapter director, prospective chapter leaders often voiced a similar concern. They wanted to advocate as concerned moms, behind the scenes, without officially affiliating themselves with Start School Later. They didn’t want the district to know who was leading the charge to return to healthy hours! Choosing this route robs an advocate of a support system with others across the nation that comes from being part of a larger organization. As a chapter leader, one learns how to navigate the tough questions while receiving guidance and resources. Start School Later provides a foundation to healthy hours advocacy so advocates can avoid re-creating the wheel in each and every district. This foundation provided the platform for the recent legislative and historical success in California. One learns how to navigate the tough questions while receiving guidance and resources as a chapter leader. Start School Later provides a foundation to healthy hours advocacy so advocates can avoid re-creating the wheel in each and every district. As ones’ expertise in this fact-based advocacy develops, we ultimately learn that the importance of adolescent sleep is bigger than our family’s needs or our school district, but a national health crisis affecting a generation of teens.

Some are successful in affecting local change, other are not. But every email, letter, or presentation contributes to an awareness of the importance of setting school hours conducive to children’s needs. It is a long journey: a marathon, not a sprint. Truth is on our side. So take up the mantle, lead the charge, and embrace your motherhood advocacy! Debbie Owensby Moore currently leads Start School Later Texas and for many years served as Start School Later's National Chapter Director. Follow her on Twitter at @DebbieOMoore. The inside story on Fairfax County, VA's ongoing efforts to ensure safer, healthier bell times for students K-12 by Phyllis Payne, Sandy Evans, and Judith A. Owens  A recent major newspaper published a story that sensationalized shifting bell times and pitted one child in a family against another—implying that older children are somehow undeserving of sleep or our sympathy while ignoring the fact that the middle school sibling would herself benefit from the overall schedule change once she reaches high school. In particular, the reporter criticized “flipping” the bell times. The “flip” is only one of many approaches schools use to provide healthy schedules. Each community can and usually does explore a number of options when looking for that “Goldilocks solution” to balance the political resistance to change against the biological needs of the students. Start School Later’s position is to encourage districts to schedule all children to start school after 8 a.m., our leadership also recognizes that we don’t want the perfect to be the enemy of the good. None of our children should be at the bus stop before dawn. We minimized the number of years that any student would be exposed to start times before 8 a.m. Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) chose a good option with a goal to make further improvements as soon as possible—improvements that would be expedited by legislation like California’s SB328 setting parameters for all schools. We minimized the number of years that any student would be exposed to start times before 8 a.m. While the change meant that most 7th and 8th graders started around 15 minutes earlier than before for their two years in middle school, all high schoolers started 50 minutes later for 9-12th grade. Our 7th to 12th grade secondary school students all start at 8 a.m. now, a 40-minute improvement. Parents may still be sleep deprived, but like our children, our years of sleep deprivation due to school policy are more limited than they were before we tackled the problem. We don’t want the perfect to be the enemy of the good. None of our children should be at the bus stop before dawn. Importantly, students have gained substantial benefits from our new bell schedules: Published studies specific to the change in Fairfax found significant gains in sleep, mood (less depression), and more students eating breakfast before school, researchers also found reduced daytime sleepiness and self-reported drowsy driving. Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) data confirm findings from previous studies—Fewer teen drivers in Fairfax are involved in car crashes, including crashes related to distracted driving (DMV has no category for “drowsy driving”). That’s one finding that hopefully provides peace of mind not only to parents of young drivers, but also to people who share the roads with them. Phyllis Payne, MPH is a Co-Founder of SLEEPinFairfax and Implementation Director of Start School Later. Sandy Evans is a Fairfax County School Board Member and SLEEPinFairfax Co-Founder, Judith A. Owens is the Director of the Center for Pediatric Sleep Disorders at Boston Children's Hospital and Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School who has studied the process of bell-time change in Fairfax County Public Schools. Middle school and high school are already some of the most grueling years in most kids’ lives. And everything is harder, darker, sadder, and heavier when you’re tired.By Morgan Lloyd So I think we can all agree that being a teenager can really suck sometimes. Middle school and high school are notorious for being awkward, scary, and hard. These are the beginnings of the formative years of our lives. We’re shown how to be individuals, how to start being adults, how to learn. But I associate middle school and high school not with excitement of becoming my own person but with thin carpets, bright lights, and exhaustion.

Exhaustion was a badge of honor in high school. We would compare sleep horror stories, in a way competing with one another to see who was operating on the least amount of sleep. We bonded over the bags under our eyes, seeing them as proof that we were fighters. That our lives were rigorous and hard. Obviously, we were teenagers trying to be big and bad, but my point is that not only was sleep deprivation the norm: it was expected and even glorified. I was lucky if I got five hours of sleep a night. Yes, lots of homework kept me up late, but regardless of work I couldn’t fall asleep earlier if I tried. My body wasn’t ready to sleep at nine, which is around when I’d have to fall asleep to get the baseline eight hours. No teenager I know can fall asleep on command, especially not that early. So, to the teachers who tell us to “just get to bed earlier,” we know you mean well, but it’s just not that simple. Probably the most common question we're asked here at Start School Later is how many schools or districts have "made the change" or "started later." Unfortunately, this question has no simple answers.

On an anecdotal level, Start School Later maintains a list of known success stories and activity by state as we become aware of them. Other website, such as www.schoolstarttime.org attempt to do the same thing. However, none of these lists, created by individuals who happen to see information on a catch-as-catch-can basis, are comprehensive. Alas, no better lists exist. A comprehensive listing is not likely to exist in the foreseeable future. There are over 13,000 individual school districts in the USA, and close to 100,000 individual schools. These districts and schools change their hours all the time, at will, earlier as well as later, for a variety of reasons. Just because a district changes or is thinking about changing doesn't mean sleep research or student health or safety have anything to do with that decision. Just because a school moves later doesn't mean they won't move earlier the following year. And even if they did, we have no way to track that because there is no central clearinghouse of this kind of information for those 13,000-plus districts that tracks every individual school’s hours every year, and provides this data in a disaggregated form. Even if we had such a centralized clearinghouse, we still would have no way to know whether any given change was specifically due to sleep research or anything else or whether any given change is maintained from year to year. Since "later" is a relative term, it's not entirely clear which changes should be counted as "later." With districts "contemplating" a change, information is less likely to be made publicly available. The average bell time of US high schools has not changed significantly since 2007, the first year this statistic was recorded. We also know that close to 83% of US middle, high, and combined middle/high schools in the USA still start class before 8:30 a.m., and that in most states, over 75% of middle, high, and combined schools start before 8:30 a.m. Ideally, we would like to see a national or even statewide database in which both school start time and bus time data were collected annually and made available for analysis by school over time. Start School Later does not have the resources to do this collection for 13,000 districts and all the schools within them, and groups with the resources thus far have not had the motivation to collect it. One of our goals is to get state or national agencies to collect and disseminate this very data (or get a grant to do it ourselves!) because that in and of itself would work wonders in raising awareness about the nature of the problem. Over the years, various sleep researchers, have attempted to collect such data and abandoned the effort when they realized the magnitude of the task. If data collection is a means to assess the growth of the Start School Later Movement, there are better ways to assess this. These include the growing number of policy statements by leading health organizations, the increasing successful statewide legislation, the explosion in media attention to this issue, and the growth of Start School Later - as marked not only in the number of chapters and hits on the website but the recent national conference that brought together the worlds of health, sleep research, education, policy, and advocacy. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed