|

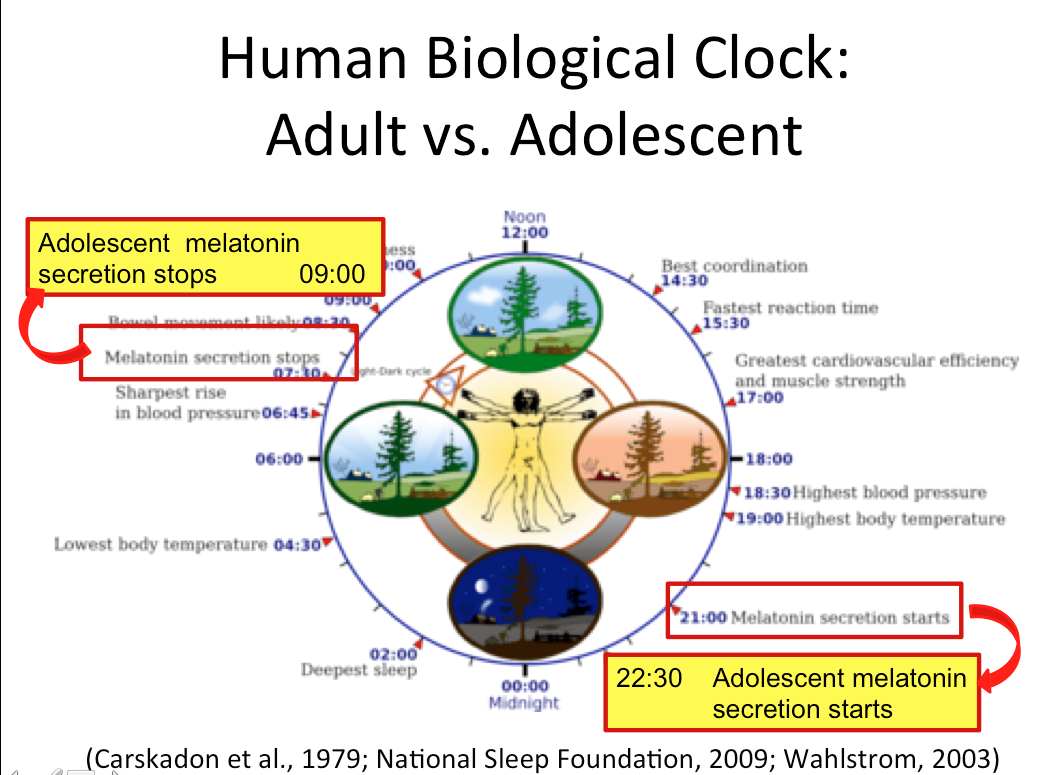

Did you ever wonder why some people bounce out of bed bright-eyed and bushy-tailed when their 6:30 a.m. alarm goes off, while others find it torturous to get up that early? Some people seem to naturally be “larks” or “owls” (or somewhere in between) and can’t do much about it. For decades, the medical community has studied why this lark versus owl difference occurs in adults. Only recently have we come to understand how it manifests in adolescents. Scientific studies reveal an internal clock in our brains that counts time and then “orders” various biological changes to occur throughout the day. For example, at night, our brain’s internal clock lowers our body temperature about 2°F and slows down our heart rate, while increasing tissue-repair and energy storage activities. In some of us, this body temperature drops early in the evening and rises again around 6 a.m., whereas in others it stays high longer and doesn’t significantly rise again until 8-9 a.m. Similarly, our body’s release of the hormone melatonin, which is critical for our feelings of sleepiness, starts later in the evening—and lasts later into the morning—in some people than others. The increasing temperature and dropping melatonin levels we experience in the morning are what makes us wake up and feel alert. Those whose body temperature increases and melatonin drops early in the morning are “larks,” and those who shift later are “owls”. Amazingly, neuroscientists have uncovered the exact molecular basis for this difference, and it all revolves around how accurately our "brain-clocks" count time. Just like some people are tall and some are short, some people’s clocks run faster and some slower. Why does all this matter for teenagers and getting up for school? Over the past 20 years, scientists have proven something many of us knew it as teenagers. During the developmental changes of adolescence, nearly everyone’s clock slows down. Your 7-year-old who woke you up way before you were ready is now a 14-year-old that you can’t get out of bed in the morning. It isn’t because she’s lazy, or because she stays up too late. She's still awake bopping around the house because she just isn't sleepy yet--just ask her! Scientist have actually measured this melatonin delay and body temp shift and guess what? Essentially, almost all of us become “owlier” during adolescence, not due to social pressures (though sometimes those don’t help) but to natural developmental shifts that delay the changes in our brains’ “sleepy” cycle almost 2 hours later. This phenomenon isn't unique to human beings, other adolescent mammals experience this delay too. We can make kids get up early anyway, of course: after all our generation had to do it. However, research shows cognitive skills, including the ability to learn and remember new information, also vary throughout the day. This means we didn’t learn as much as we could have if school started later. If we want our students to do their best, we should teach them during their “day,” not get them up at a time that to their body clock ensures feels like the middle of the night! Sending kids to school before they’re awake (and/or before the sun has risen) is also is dangerous. Research shows that when high school is moved later, students are less likely to be in car accidents and more likely to survive high school. And the myth that starting school later will impact school activities is just that, a myth. In the communities that have made the changes, people did what our species has always done in times of change, they adapted. This is true even in the case of athletics; schedules were accommodated and team performance actually improved. As parents, we're pretty adept at making changes for our children, think about how often you adapt for seasonal schedules. If we were in a society that didn’t yet have schools and we asked our scientists and learning experts, “when is the best time to start school?” they’d say “after 8:30 a.m.” This is just what the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends. As a parent, and a neuroscientist I know that starting school later is better for our kids’ learning, for their safety, and for their health. I hope by reading this, you have a better understanding of that too. AuthorSarah Leupen has a Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Northwestern University and teaches biology at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC). She has two middle-school aged children. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed